Monitoring Guardianships

The court’s duty to protect the well-being of an individual does not end when it appoints a guardian. Courts have an ethical, moral and legal duty to monitor guardianship cases given that establishing a guardianship is a significant curtailment of civil rights. The National College of Probate Judges Court Standards on monitoring state, “The safety and well-being of the respondent and the respondent’s estate remain the responsibility of the court following appointment.” One judge observed, “In reality, the court is the guardian; an individual who is given that title is merely an agent or arm of that tribunal in carrying out its sacred responsibility.”

Course: Guardianship Monitoring Protocol

With a monitoring protocol, the court can identify guardians who are struggling, guide a guardian who needs assistance in fulfilling their duties, and the court can stop a guardian from using their court appointed authority to abuse, neglect, or exploit an individual. In this interactive series, court personnel will learn how to use the monitoring protocols, applying them to fictional case reports.

The National Probate Court Standards (Standard 3.3.17) and Recommendations adopted at the Third National Summit on Guardianship (Recommendation #2.3) are consistent in what constitutes basic monitoring practices:

Probate court should monitor the well-being of the respondent and the status of the estate on an on-going basis, including, but not limited to:

- Determining whether a less restrictive alternative may suffice;

- Ensuring the plans, reports, inventories and accountings are filed on time;

- Reviewing promptly the contents of all plans, reports, inventories and accountings;

- Independently investigating the well-being of the respondent and the status of the estate, as needed; and

- Assuring the well-being of the respondent and the proper management of the estate, improving the performance of the guardian/conservator and enforcing the terms of the guardianship/conservatorship order.

Judicial actions & monitoring strategies

This video offers an overview of monitoring strategies and best practices.

Judicial officers and the court should consider the following strategies after appointing a new guardian. These actions can take place initially after appointment or throughout the life of a guardianship case. There may be overlap in the time period in which some of these responses are implemented and some may not be applicable at all.

The monitoring process begins with the establishment of a guardianship and the submission of initial reports. Increasingly, there are greater demands that guardians and conservators submit prospective care plans and estate management plans as well.

The National Probate Court Standards identifies some basic timeframes and expectations for the submission of reports (Standard 3.3.16), which are summarized below.

Guardianship filings

Required at the hearing or within 60 dates:

- Guardianship plan

- Report on the respondent's condition

Notices required by the court:

- Respondent's intended absence from the court's jurisdiction in excess of 30 days

- Any major anticipated change in the respondent's physical presence (residence)

Follow-up reports:

- Annual updates

- the respondent's condition;

- the services and care being provided to the respondent;

- significant actions taken by the guardian; and

- expenses incurred by the guardian.

While annual updates are required by statute in nearly all states, courts have flexibility in terms of requiring more frequent updates and additional information in cases that may benefit from an increase in oversight.

Courts should have standardized forms that are readily available online. Ideally, forms should be available at the state level and be easily downloadable and fillable, such as those provided by the California Judicial Council (see probate forms). The Minnesota Judicial Branch has online portals for guardianship and conservatorship reporting. In addition to standard forms, courts should consider requiring emergency plans and prospective care plans. Sample forms also can be found in the appendix of Guarding the Guardians: Promising Practices for Court Monitoring.

Resources

DCM is a technique that allows courts to tailor the case management process to the requirements of individual cases. Rather than using a first-in, first-out basis that treats all cases identically, DCM uses a triage approach to assign cases into different categories and hence, case management tracks to address abuse, neglect and exploitation. There are two common types: case-based and systemic review.

Examples:

Arizona: Improving Protective Probate Processes for Probate Case in Maricopa County Superior Court in Arizona.

Idaho: Idaho courts utilize a Differentiated Case Management tool that triages Guardianship cases into three monitoring tracks: low, medium, high. It is a questionnaire (download) that is to be completed on each guardianship case to assist in assigning monitoring efforts to the highest risk cases. Instructions can be found here.

Differentiated case management (DCM) in probate cases may be the wave of the future. Probate DCM to Protect Vulnerable Adults demonstrates how DCM can be used both before and after appointments of guardianships/conservatorships. The article is based on an assessment of the Probate and Mental Health Department of the Maricopa County Superior Court in Arizona.

The following list summarizes features of DCM noted in the article and Maricopa County assessment.

Phase DCM & actions

Pre-Appointment

Uncontested Petitions:

- Appointment of Fiduciary

Contested Petitions:

- Hearing on a Contested Petition

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- Settlement Conference

- Trial on Contested Petition

- Appointment on Fiduciary

Post-Appointment

Minimum Risk:

Biennial telephone interview with respondent

Moderate Risk:

- Annual in-person visit with respondent

Maximum Risk:

- Combination of actions, including case compliance audit or forensic investigation

DCM can be readily applied at the pre-appointment stage as contested petitions can be readily identified by the court. However, the practice of separating guardians and conservators into appropriate risk levels after the appointment is challenging (see "Red Flags"). Included in the Arizona Supreme Court's Committee on Improving Judicial Oversight and Processing of Probate Court Matters Final Report is a risk assessment form (Appendix D) that provides a guide for placement of guardians/conservators into Triage Model "A" or Triage Model "B." Triage Model "A" calls for mandatory post-appointment monitoring and a visit from a volunteer guardian monitor within two years of the initial appointment. Triage Model "B" provides full judicial discretion in post-appointment monitoring activities.

The use of DCM in probate cases holds great promise. Unfortunately, a true risk assessment tool based on an empirical study identifying statistically validated factors does not exist. Rather, "red flags" that form the basis of assessment tools derive from anecdotal experiences. Thus, some caution must be used to determine the category of risk most appropriate to each case.

Resources

- NCSC's Caseflow Management Resources

- Court Guide to Effective Collaboration on Elder Abuse

- This report summarizes NCSC’s evaluation of the Maricopa County Superior Court’s Probate Department, including their use of differentiated case management (DCM) and a Probate Evaluation Tool (PET) that is used to assign guardianships into low, medium and high monitoring levels.

Actively monitor cases

Track cases and ensure reporting compliance

Ensure that well-being plans and reports are filed on time by using checklists and tracking tools.

Well-being reports may be referenced by many different names, but they all provide a way for the court to monitor the welfare of individuals under guardianship. The reports are filed by the guardian, typically on an annual basis, to provide “descriptive information on the respondent’s condition, the services and care being provided to the respondent, significant actions taken by the guardian and the expenses incurred by the guardian.”

If reports are not filed on time, take action: Court orders - Hearings - Sanctions

Use a review protocol and compliance checklists

Review promptly the contents of all plans and reports.

With a monitoring protocol, the court can identify guardians who are struggling, guide a guardian who needs assistance in fulfilling their duties, and the court can stop a guardian from using their court-appointed authority to abuse, neglect, or exploit an individual.

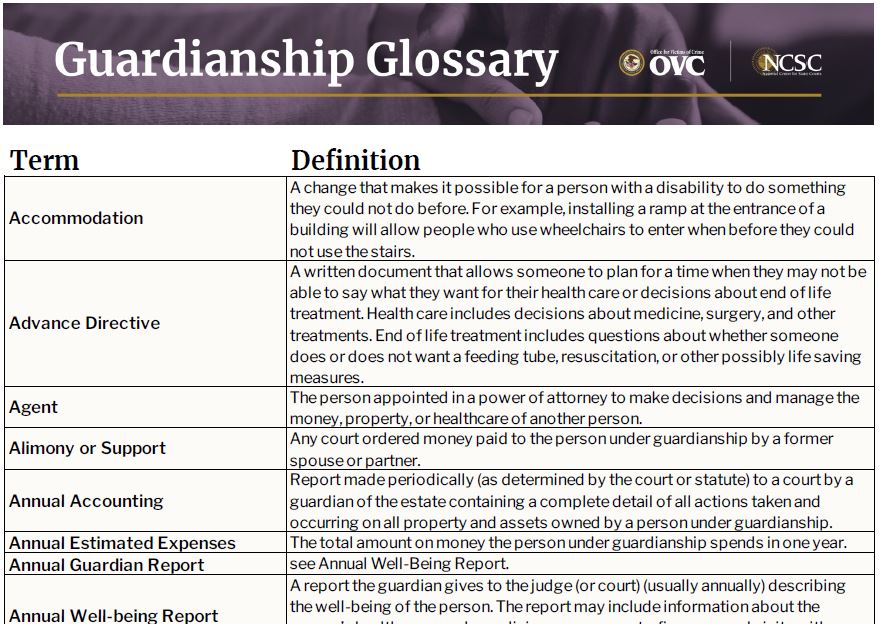

To support courts in monitoring guardianships, NCSC created a protocol for monitoring the well-being of the person under guardianship. This protocol provides a template for court and clerk staff (including but not limited to judicial officers, judicial staff, court clerks, auditors, and volunteers) to be used as a screening document to assist reviewers in flagging reports that need further action. Some examples of questions asked in this template include:

- Is the report identical to the previous year’s report?

- Does the well-being report speak to the mental, physical, and social condition of the person subject to guardianship?

- Are there any concerning points in the report about the guardianship?

- Is this guardianship still appropriate?

If an examination of the report shows discrepancies, lack of documentation, or suspicious activity, consider:

- Referral for audit

- Assignment of court visitor or guardian ad litem

- Hearings

NCSC Protocol Supplemental Resources:

Additional form and checklist examples:

- Auditing and compliance checklists example: Pennsylvania Guardianship Tracking System (GTS)

- Travis County, TX: Guardianship Annual Accounting Checklist

- National Guardianship Association: NGA'S Standards of Practice Checklist

Needs assessment

Assess the functionality, trajectory and protected needs of the existing guardianship. The guardianship may no longer be needed or may benefit from a restoration of rights with supported decision-making. Tool: Capacity assessment instruments

Well-being checks

Electronic filing

Allow court-appointed guardians to submit personal well-being reports and the Affidavit of Service electronically.Court Visitor/Investigator

Results from a survey of judges and court managers on guardianship issues (Adult Guardianship Court Data and Issues) demonstrated the inability of many courts to provide basic data on guardianships and conservatorships and was the basis for the following recommendation:

Courts should explore ways in which technology can assist them in documenting, tracking and monitoring guardianships.

Recommendations from the Third National Guardianship Summit (Recommendation #2.5) encourage courts to use available technology to:

- Assist in monitoring guardianships

- Develop a database of guardianship elements, including indicators of potential problems

- Schedule required reports

- Produce minutes from court hearings

- Generate statistical reports

- Develop online forms and/or e-filing

- Provide public access to identified non-confidential, filed documents.

While many state courts are unable to properly monitor and document guardianships, a number of courts are advancing the field by applying technology to these case types. Generally, software applications can be used to enhance the court's responsibilities in overseeing the guardianship process and to identify guardian activities that appear to be out of the norm.

At its basic level, software can be used to create a "tickler" system that primarily reminds the court and notifies guardians of due dates of particular reports, such as annual accountings. At a higher level, financial-based software can be used to detect anomalies in conservatorships. Several examples showcase how technology can improve the guardianship process and court oversight.

Example: Florida's guardianship reporting software

Florida's 17th Judicial Circuit (Broward Country) uses guardianship reporting software that includes the following "smart forms", which can be e-filed:

- Annual guardianship plan

- Simplified annual accounting

- Application for appointment as guardian

- Disclosure statement

- Employee statement with a fiduciary obligation to a person under guardianship

- Annual guardianship investigation checklist – non-professional

- Annual guardianship investigation checklist –professional

- Professional guardianship checklist – additional appointments

- Inventory

- Petition for order authorizing payment of attorney's fees and expenses

- Petition for order authorizing payment of compensation and expenses of guardian

The goal of the software is to reduce paper logistics, offload costly data entry and reduce errors and redundancy. The software offers judges and court staff flexibility in searching particular items and running reports. For example, reports could be run on cases where the visitation of the respondent was not completed once per quarter or on cases where income increased or decreased by a specific percentage when compared to the prior accounting.

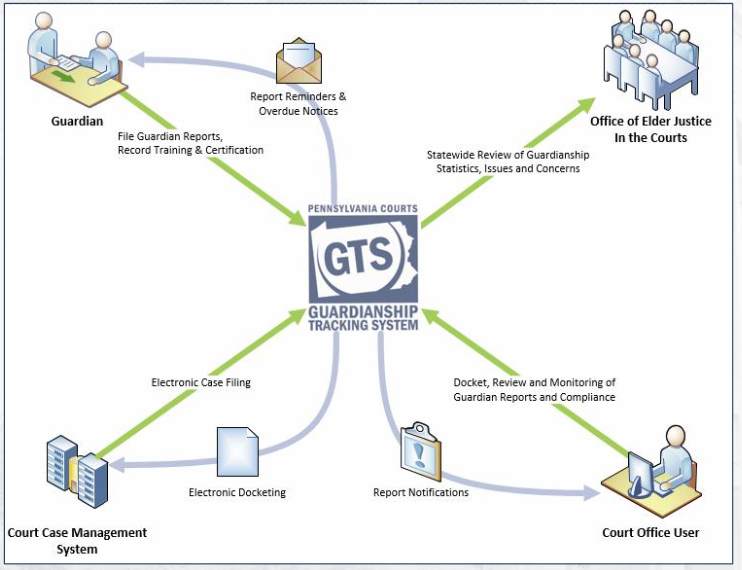

Example: Pennsylvania's Guardianship Tracking System (GTS)

Pennsylvania uses a statewide tool for courts to manage guardianship cases and track guardian compliance with annual reporting. It combines several critical functions:

- E-filing for guardians

- Statewide repository of guardians

- Compliance tracking and electronic notifications (reminder and overdue notices)

- Statewide alerts about guardians (in cases of abuse, neglect, or financial exploitation)

- Automated flag logic

- Statistical reporting (with data on caseloads, petitioners, attorney representation, guardian compensation and asset protection)

Additional resource

Consider Well-Being Red Flags that might indicate:

- The person no longer needs a guardianship or needs a change to the type or scope of guardianship

- There are concerns about the person’s safety or well-being

- The guardian is struggling

- The guardian does not cooperate with the court and/or not enough information has been provided to assess those items

For red flag examples and more information, review:

To see protocols and red flags related to Accounting reports, go to the Review Cases section of our Monitoring Conservatorships page.

Further Examples:

- Pennsylvania: Guardianship Tracking System (GTS)

- Travis County, TX: Guardianship Annual Accounting Checklist

- National Guardianship Association: Standards of Practice Checklist

Be prepared to spot evidence of financial abuse in court records. In particular, be aware of missing accounts, as they tend to be an early signal.

For more information, see Monitoring Conservatorships.

When abuse, neglect, or exploitation is suspected, please refer to the Judicial Complaint Response Protocol.

Probate court staffing and general training remain topics of concern for many courts. This issue can be particularly challenging in courts that do not have a specialized probate division or seldom hear guardianship cases and for courts in a number of states that have lost resources in response to budget cuts. This has resulted in greater reliance on volunteer monitoring programs, or in the worst-case scenario, the inability to actively monitor guardians according to standards.

Compensate for inadequate levels of staffing and resources by developing volunteer monitoring programs, overseen by a qualified coordinator, to supplement court staff.

Examples & resources:

The American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging describes volunteer monitoring programs, as a win-win solution for the courts and those placed under a guardianship. The Commission offers a three-part Handbook on Volunteer Guardianship Monitoring and Assistance to help courts establish volunteer monitoring programs:

Additionally, the National Center for State Courts created an implementation guide for Georgia that contains information that may be helpful to courts considering the development of such programs.

Examples of Volunteer Monitoring Programs:

- Ada County, Idaho

- Snohomish County Superior Court, Washington

- Lake County Probate Court, OhioTarrant County, Texas

The Concept of Eldercaring Coordination

Utilize 'Eldercare Coordinators' in high conflict guardianship cases.

The Association for Conflict Resolution (ACR) created a task force on eldercaring coordination, which is described as a dispute resolution option specifically for those high conflict cases involving issues related to the care and needs of elders.

In 2014, the ACR Task Force published its guidelines for eldercaring coordination, which includes qualifications and resources for individuals who serve in the capacity of Eldercare Coordinators

Additional resources

Without enforcement, guardianship and conservatorship orders hold little authority. Enforcement can take a number of forms, including suspension, contempt, removal and appointment of a successor guardian or conservator. The National Probate Court Standards (Standard 3.3.19) directs courts to enforce its orders by taking appropriate actions and moreover, to take timely action to ensure the safety and welfare of a respondent upon learning of a missing, neglected or abused respondent, or where the respondent's estate is endangered. The Standards urge courts to remove the guardian or conservator and appoint a successor when a guardian/conservator is unable or fails to perform the duties set forth in the appointment.

According to the Standards, courts should not be passive, but rather, prioritize the safety and well-being of the respondent. Prompt hearings are called for when reports are not filed in a timely manner, are inadequate, or complaints suggest concerns related to the respondent's well-being.

The Standards offer the following examples of court sanctions in response to issues that arise:

Contempt citation

- Issue: Failure to file required reports on time after receiving notice and appropriate training and assistance

Notice of a show cause hearing to probate court in new jurisdiction

- Issue: Guardian or conservator has left the court's jurisdiction

Disciplinary action for attorneys

- Issue: Attorney guardians may have violated their fiduciary duties to the respondent

Suspension and appointment of a temporary guardian

- Issue: Failure to perform duties. Welfare, care, or estate of the respondent require immediate attention

The due process rights of the guardian should be protected when initiating sanctions. The removal of a guardian because of his or her inability or failure to fulfill the responsibilities should be followed by an emergency appointment of a temporary guardian. The court should then order an investigation to locate the guardian and examine the person's conduct, with appropriate sanctions ordered where appropriate.